For the Cult issue, it’d be pretty weird if we didn’t interview a cult specialist to find out how to start a running cult. That was the planned approach for this interview with cult deprogrammer Rick Ross: make out like we’re having a friendly chat about his work, but really I’m sucking info out of him to help me launch a running cult I’m calling ‘The Sisterhood of the Miraculous Fast Boy’ (The Sisterhood of the Miraculous Fast Boy is in no way affiliated with Satisfy, POSSESSED magazine, or anything, really, I’m just making light of a very dark and serious subject so you don’t get too bummed out).

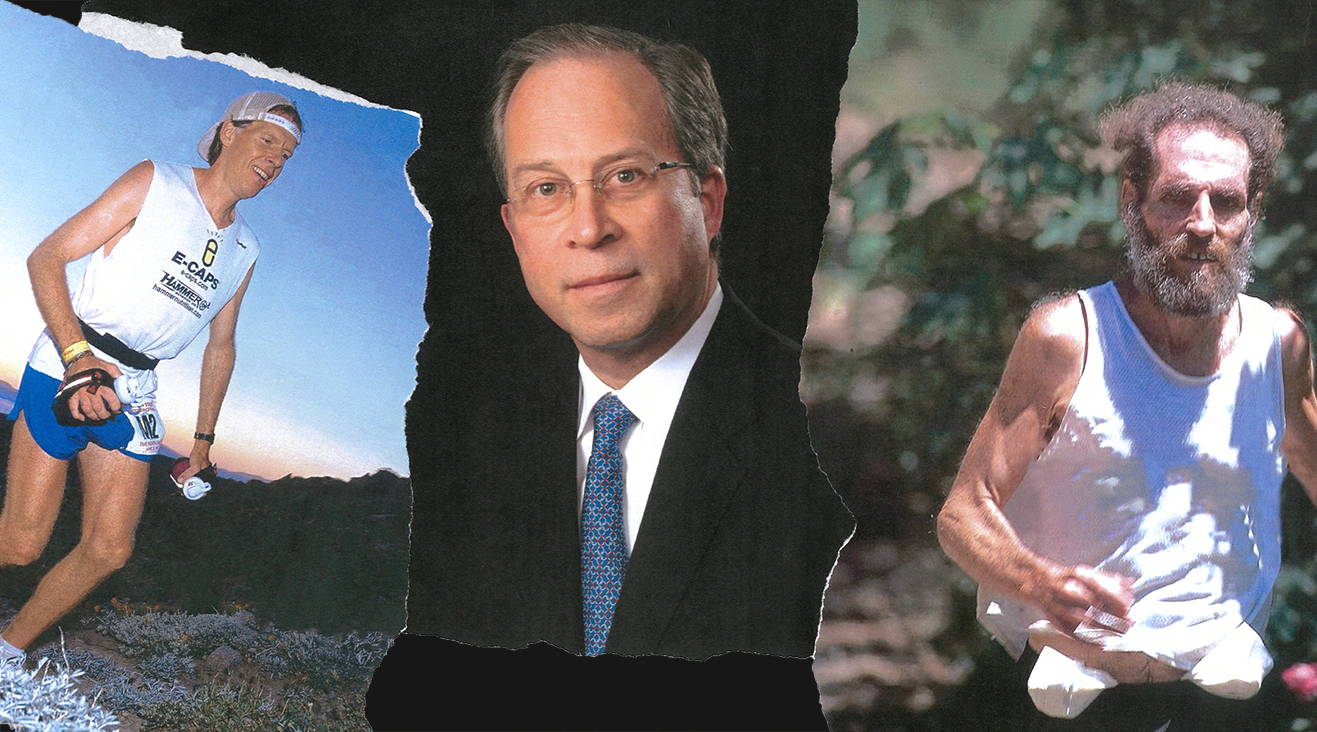

So, I called up Rick. As it happened, there wasn’t much room for gagging around about cults because, well, cults aren’t very funny. Plus, someone already established a genuine running cult in the 1990s called The Divine Madness Running Club, which is what we mainly talked about. A little about Rick: he’s an American cult deprogrammer, the founder of the non-profit Cult Education Institute, author of Cults Inside Out, and he’s saved more lives than you and I have done laps of the park. Let’s meet him.

Hey, Rick Ross!

Hello. So, you want to talk about The Divine Madness Running Club?

I do, but first, how long you’ve been a cult deprogrammer?

I’ve been doing this for forty years.

Wow. How’d you get started?

Well, my grandmother’s nursing home was targeted by a bizarre religious group that wanted to recruit elderly people. They had members of their group covertly get jobs on the nursing home staff, and they started to basically work their plan in the nursing home, which was to target elderly people.

Creepy.

Yeah. And my grandmother was 82, and she was accosted by one of these people. I found out about it; I was extremely concerned and, quite frankly, angry. I went to the director of the nursing home, and eventually we found that there were five members of this group on the paid staff, and they were all fired. But that led to me becoming an anti-cult activist and community organizer in Phoenix, Arizona, which led to committee appointments, national committee appointments, and eventually it became a full-time gig. Which certainly wasn’t my plan.

What were you before you became a cult deprogrammer?

I was vice president of a large scrap metal and wrecking yard owned by my cousin.

You’re kidding.

I’m not. And I was very happy working there—I loved working there—but I transitioned from working in the salvaging business to salvaging people. I started doing volunteer intervention work, then I worked for a social service agency, an educational bureau, and by the end of the ‘80s, I was doing private cult intervention work across the United States and internationally.

How many interventions have you done?

Over five hundred now.

Wow. And how many active cults are there in the world?

It’s endless.

Really?

Yeah. And especially now that they’re able to recruit online and through social media. It’s much more pervasive now than it ever has been in my career. Increasingly, I’m dealing with people who were recruited online, indoctrinated online, gave their money online, and I’ve even done interventions over Zoom online.

'...how many active cults are there that we know of? According to one cult-watching group, there are ten thousand in North America alone.'

Crazy.

But how many active cults are there that we know of? According to one cult-watching group, there are ten thousand in North America alone.

Ten thousand in the U.S. Are you serious, Rick?

Yeah, ten thousand in North America that have been documented through complaints.

That is bananas.

I learn about a new group almost every day. Keep in mind, a cult could be a handful of people or it could be thousands of people. They vary in size. And they vary in guise, in the mask they wear. There are just so many of these groups. But they all basically have the same structure, dynamics, and behavior patterns.

Right.

One of the things to understand about cults is that they’re not all equally destructive. For example, there might be a group that simply wants money, free labor, as much as they can garner, and they just want to make money and manipulate people to make money. And we see that in multi-level marketing schemes that are cult-like, pyramid schemes, and we’re now seeing it in cryptocurrency. So, some groups are after money. But the groups that want total and complete control over people, isolating them socially, often in compounds, those are the most sinister and the most dangerous.

Of course.

So, when you see a group that is completely cut off from the outside world—with filters set up for all communication—that is the most frightening incarnation of a cult. And some groups don’t start out there—they evolve to that point, as Jim Jones did with Jonestown, or as Paul McKenzie did with the Good News International Church in Kenya. So, the most dangerous groups are socially isolated, and information and access to the outside world is tightly controlled by the leader. And we see those groups ending badly over and over and over again, in one tragedy after another.

Okay. The Divine Madness Running Club, founded by Marc Tizer—aka ‘Yo’—in Boulder, Colorado, in the 1990s. What can you tell me about this group?

Well, Tizer is a self-styled running coach. He has no formal training. He claims to have learned what he knows anecdotally through television and observation. Tizer represents what all people who have been called ‘cult leaders’ represent: a charismatic personality who rules over a group of people with absolute authority and zero accountability.

Right.

So, what you see in any destructive cult are three core elements. One: an absolutely authoritarian leader that controls the group and becomes an object of worship. The leader can say and do nothing wrong. The leader is always right and has no checks and balances for their power. Second: that leader uses identifiable thought reform and coercive persuasion techniques to gain undue influence over their followers. And then number three: the leader uses their influence—acquired through this process of indoctrination—to exploit and ultimately harm the people under their sway. You could call those three elements the nucleus for defining a destructive cult.

'Tizer is the leader, the absolute authority figure, and if you disagree with him—you’re wrong.'

Okay.

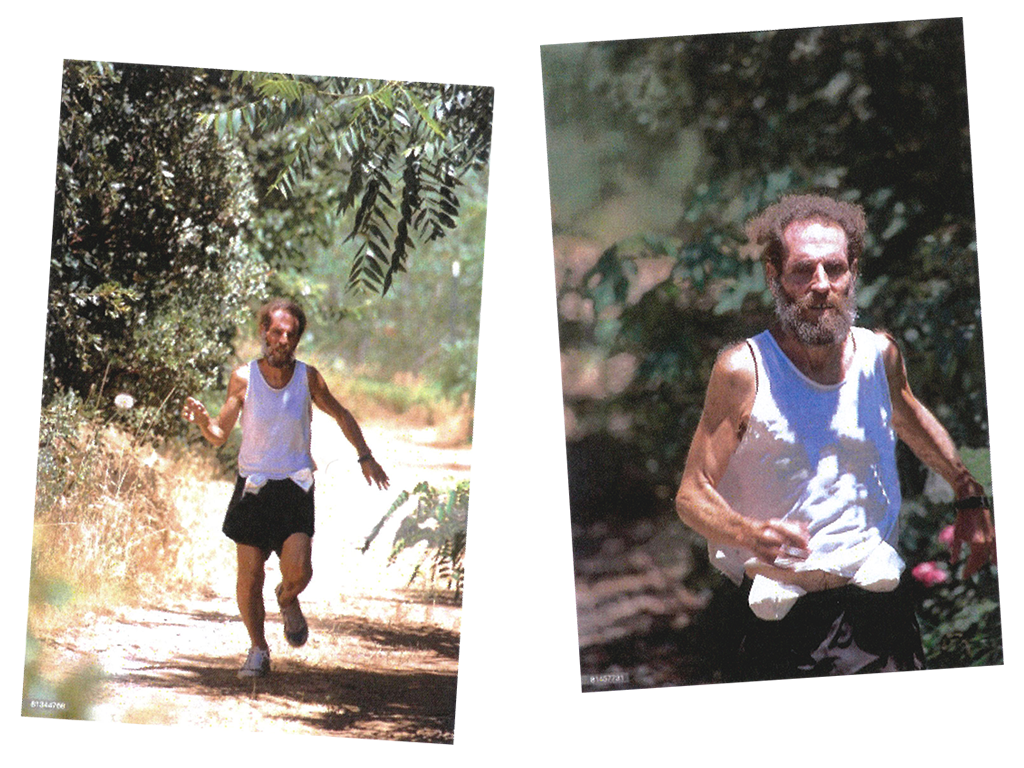

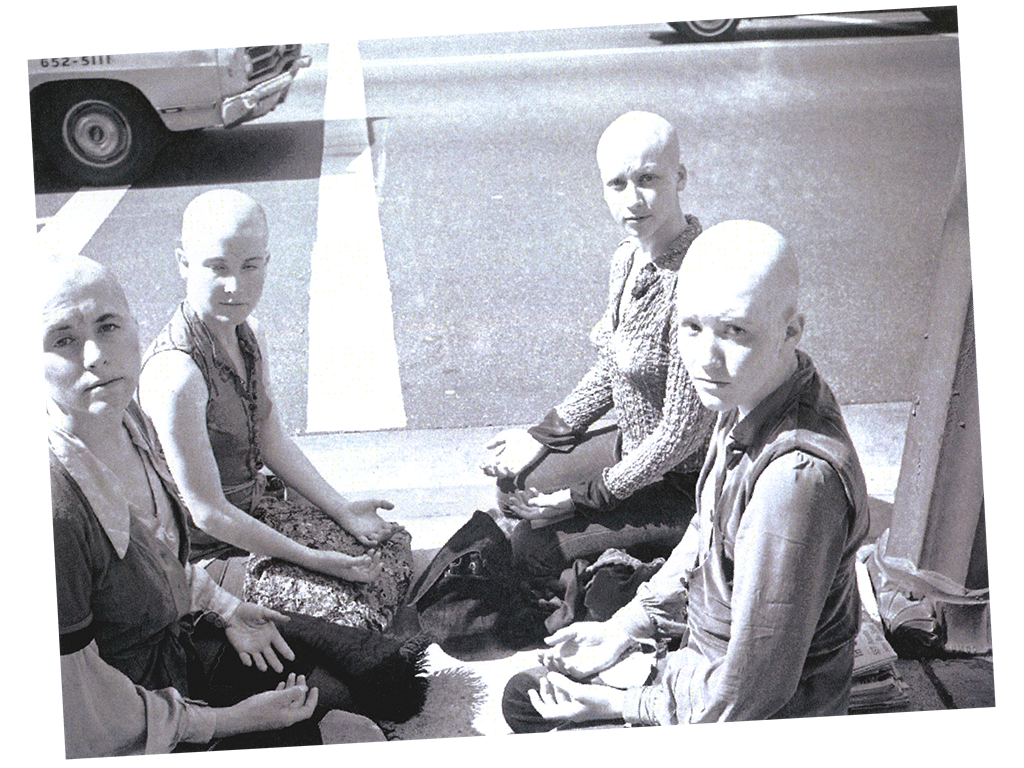

So, Tizer is the leader, the absolute authority figure, and if you disagree with him—you’re wrong. There’s no legitimate reason to leave the group, and you’re a loser if you leave the group, you’re bad if you leave the group, etcetera. So, Tizer is the all-powerful leader. He socially isolated his followers; they lived together, ate together, partied together, ran together; everything was in the group in a kind of alternate reality that was completely controlled by Tizer. And as I understand it, he still has that power over his remaining followers.

In New Mexico, apparently.

Right.

It’s hard to imagine a running group being something harmful.

Well, people died, people were exploited, damaged, and they sued him for intentional infliction of emotional distress. By many accounts, he is a horrible and abusive leader, and it was all about power, control, self-aggrandizement, ego gratification, etcetera.

I read that he had his followers run 120 to 130 miles (195—210 kilometers) per week, and when they weren’t training, they were subsisting on gruel or getting drunk! Drinking alcohol and partying, but also running 130 miles per week. That’s madness.

It is. And the thing is, he was controlling their communication, their socialization. So, they were isolated, they weren’t in touch with family or friends—he cut them off. Because the more extreme the demands of the leader, the more extreme the social isolation. What Tizer did, and what many of these leaders do, is they don’t want their followers to go to anyone for a second opinion; they don’t want anyone else to be able to give them feedback, and in that sense, it’s a bubble world completely controlled by the leader. And that’s how Tizer ran the group and probably still does with whoever remains.

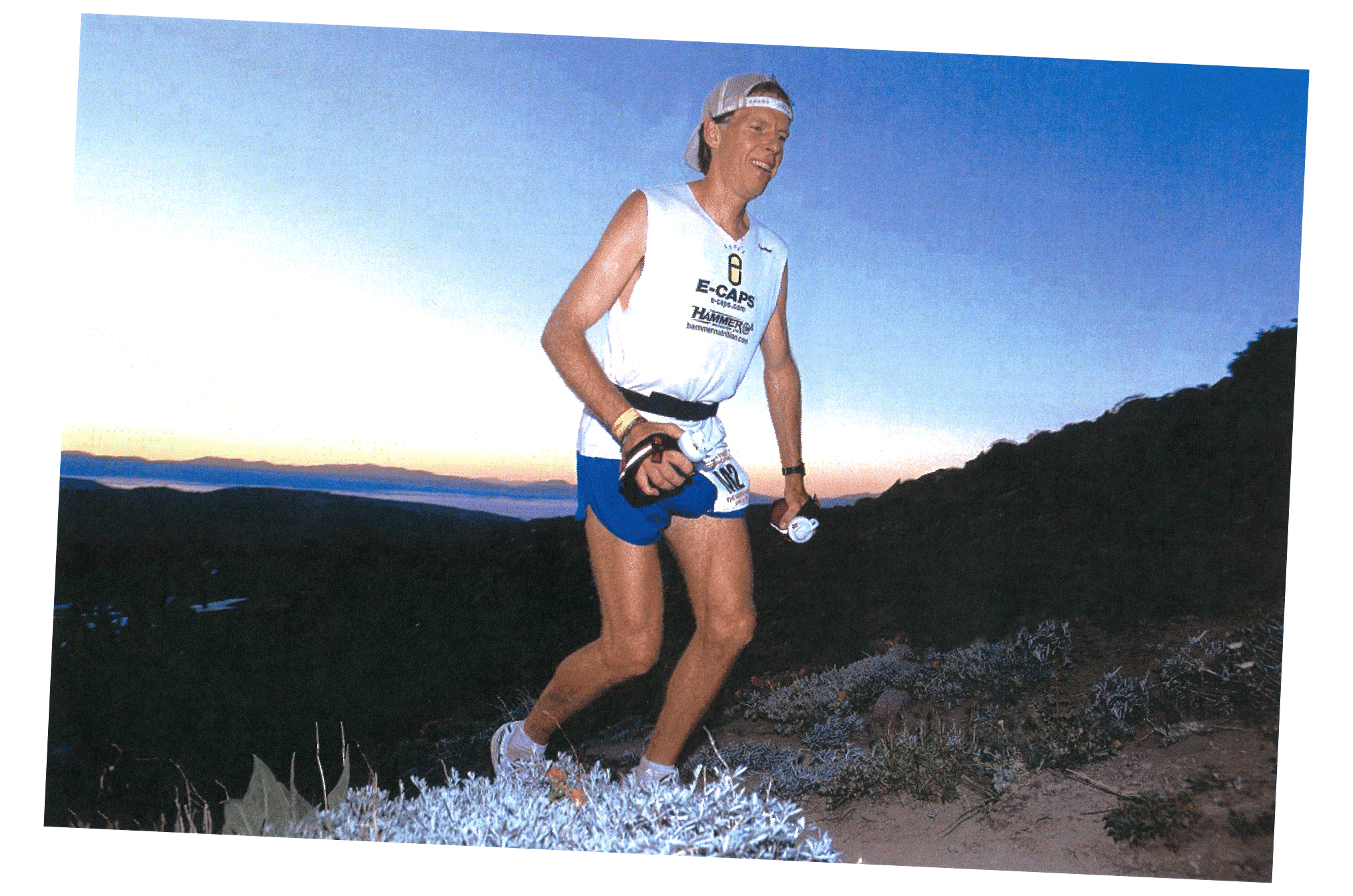

I think it’s very interesting that he kept his followers hidden away from the outside world in order to control them, but then he entered them in races—and they win! One ex-member, Steve Peterson, placed first at Leadville (a 100-mile trail race) five times between 1996 and 2001!

Right.

'I mean, that was really what it was all about: these people constantly contributing their training success, their racing success to Tizer.'

So, he’s isolating them, putting them through training hell, and then entering them in races—and they’re winning (four members of Divine Madness finished among the top 15 at Leadville in 1996). Which can’t be good because he’s drawing attention to the group.

Well, I mean, when people drop dead, it doesn’t look good. One member (Mark Heinemann) died of pneumonia. Certainly, they must have seen symptoms of his illness, and yet he didn’t get proper medical attention and he died. And the family that survived him was devastated. Tizer is like so many of these leaders in that it’s all about him. Most of the leaders I deal with are intensely narcissistic; what they feed on is self-aggrandizement, and how Tizer did it, he had these people running for him, winning for him, and praising him. I mean, that was really what it was all about: these people constantly contributing their training success, their racing success to Tizer. And then him—by virtue of that—holding himself as a kind of ultra-running guru. And another thing that’s interesting about Tizer and his group is that we often times look at cults and we say, ‘Oh, well, they’re a new religious movement, they’re just new, they’re different, it's just religion.’ But I think what the Tizer group shows is that it doesn’t have to be about religion. It can be about politics, philosophy, martial arts, dieting, multi-level marketing, cryptocurrency, and even running!

It can be about anything.

Right. Everything I just said, I could point out a cult that is based on that theme. Now, religion is the most prevalent theme, and I strongly suspect it’s because of the tax advantages.

Is it true that anyone and everyone can be sucked into a cult?

Absolutely, given the right set of circumstances. And if there’s a single narrative running through these cult victim stories that I deal with, it would be, ‘I wasn’t happy, I was going through a rough patch, and at that point, someone I trusted—or thought I could trust—approached me.’

Right.

And that could be a co-worker, a family member, a romantic interest, a fellow student, and this person introduces you to the group. And you think it must be good because they said it’s good, they’re already true believers. But they don’t tell you everything—they only tell you a bit about it, and as you become more involved, things change, but by that point, you’re indoctrinated. You’re so involved, and the group has cut you off from reality testing and being able to think critically, and then it’s too late.

You’re gone.

Right. But then there are cases where people will be perfectly happy when they’re recruited.

But do you kind of have to be a just little bit dopey to get tricked?

Listen, I can tell you I’ve deprogrammed five medical doctors. Five. One was an orthopedic surgeon, one was anaesthesiologist... I mean, it can happen to anyone. I work with people who went to ivy league schools. I just worked with a young man who graduated with honors from one of the ivy league schools in the United States. He scored in the 90s in the MCAT test, but he was going to give it all up to become a member of an ashram in India after attending a retreat in the U.S. run by the guru.

'I’ve deprogrammed five medical doctors. Five. One was an orthopedic surgeon, one was anaesthesiologist... I mean, it can happen to anyone.'

Is he good now?

Yes. He’s out of the group and has been accepted into medical school. So, you don’t have to be a dummy to fall victim to a cult.

Okay, one last question: how do you know if you’re in a cult, specifically a running cult?

Well, you would ask yourself, is there a guru at the centre of this running club? And is this guru the defining element and driving force of the group? And what accountability does that leader have? Can I criticize the leader? Can I challenge some of the basic assumptions of the group, such as the training prescribed by the leader? And is it unthinkable to question the leader? If people leave, how are they treated? Am I isolated? How isolated am I? Do I still have my own life?

And, come to think of it, how many times have I won Leadville?

[Laughs] Exactly.

Thanks for your time, Rick Ross.

You’re welcome. Great chatting with you.